THE ‘ARTISAN BOTANIST’ SAMUEL GIBSON: A LENGTHY ORNITHOLOGICAL LETTER

THE ‘ARTISAN BOTANIST’ SAMUEL GIBSON: A LENGTHY ORNITHOLOGICAL LETTER

GIBSON, Samuel (1793–1849)

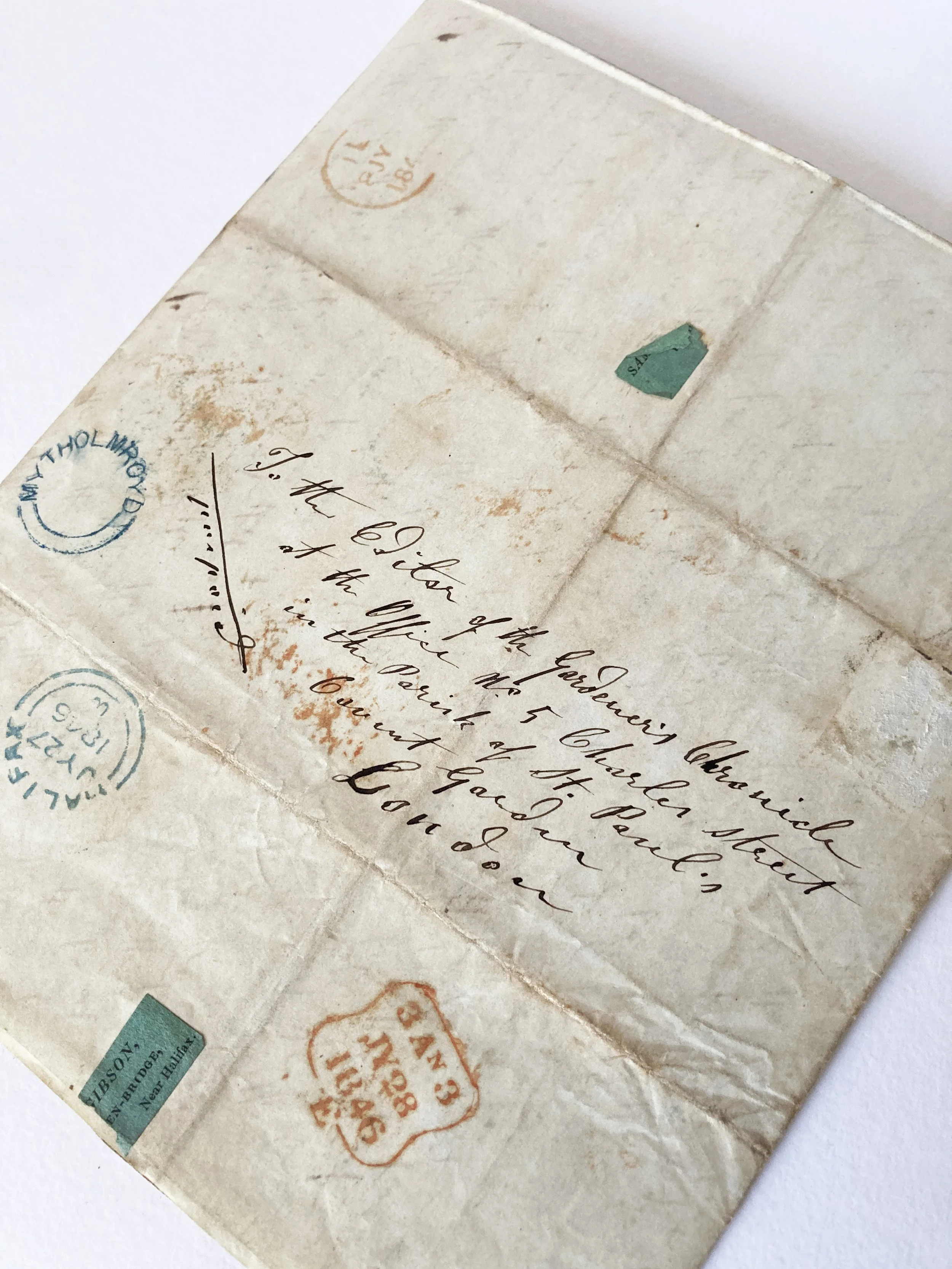

Autograph letter signed, to the editor of the Gardeners’ Chronicle, with extensive comments on the habits of the nuthatch (27 July 1846)

A FINE ORNITHOLOGICAL LETTER FROM A WORKING CLASS AUTODIDACT

3pp., on a bifolium; 188 x 231mm (folded).

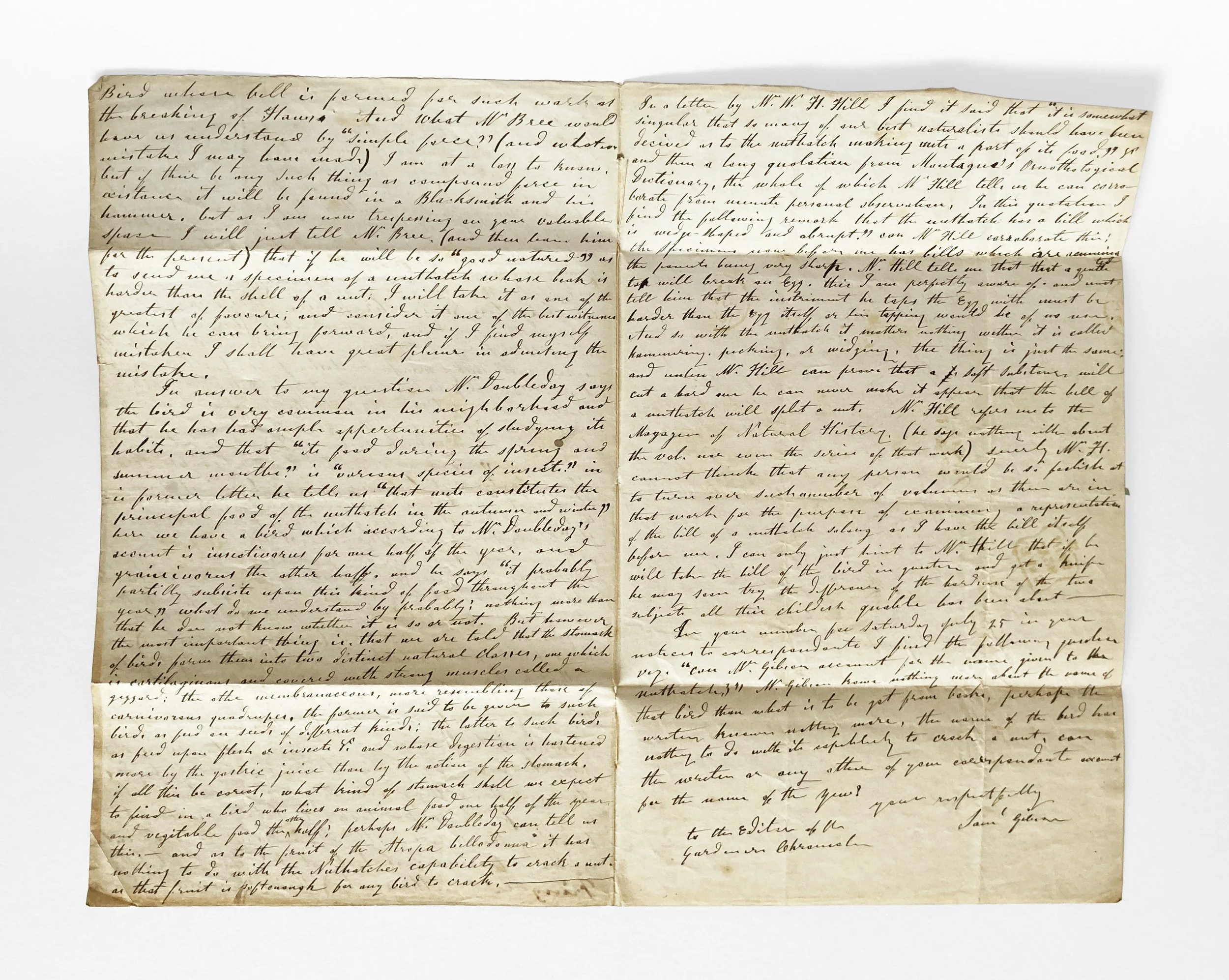

A letter full of excellent scientific content, addressed to the editor of the Gardeners’ Chronicle, by the artisan-botanist Samuel Gibson, who by this point was well established as an expert naturalist – in addition to pursuing his craft as a whitesmith.

From the Gardeners’ Chronicle for 1846 we find that Gibson had turned his attention to ornithology, writing anonymously at first and claiming that the nuthatch never in fact cracks nuts(!). This predictably aroused the complaints of a number of the journal’s readers – so much so that on July 25, the editor announced that the debate was closed. Yet in this unpublished letter, sent just two days later, Gibson continues the argument at great length.

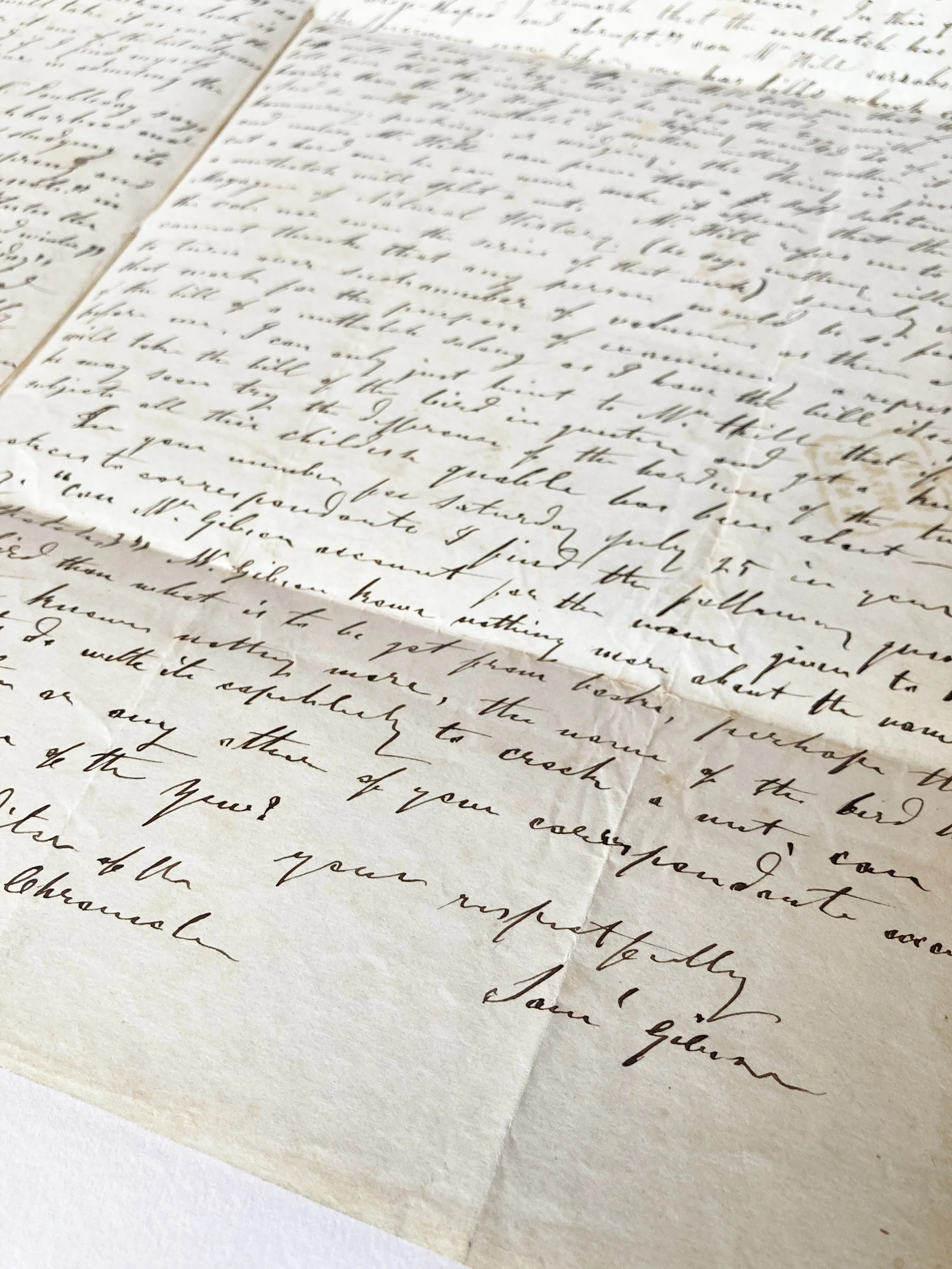

Although he might fairly be said to have lost the debate over nuthatches, his arguments are instructive. He begins with a complaint that knowledge from books is useless, granted that different authors contradict one another. Gibson gives the example of yew berries and whether they are poisonous or not, with a well chosen series of contradictory quotes from Hooker, Smith et al. ‘This is the kind of knowledge we generaly [sic] get from books,’ Gibson wryly comments.

On the question of the kind of force employed by animals, Gibson is similarly skeptical: ‘if there be any such thing as compound force in existence it will be found in a Blacksmith and his hammer’. If (as in fact is the case) nuthatches eat both insects and nuts, what, asks Gibson, is the nature of their stomach and gastric juice?

Throughout, Gibson’s point is that only a physical proof of the hardness of the bird’s beak will prove the point. Here is a rich example of Gibson’s empiricism and his rugged materialism in action.

Samuel Gibson was born at Sowerby Bridge, Yorkshire, and later worked at Hebden Bridge as a tinsmith. He became interested in botany around 1813 and is said to have kept a much used copy of William Jackson Hooker’s British Flora (1830) on his workbench. He corresponded and assisted many other naturalists, making himself an expert on sedges and mosses, as well as insects and fossil shells. In addition to the Gardeners’ Chronicle he contributed to The Phytologist, and was acknowledged in the works of celebrated contemporaries such as John Phillips, Henry Baines, Thomas Brown, Edward Newman, and Richard Buxton. At the time of this letter he had been forced by injury into retirement from his work as a smith, and was running an inn and natural history museum at Mytholmroyd, though this was shortly to close owing to lack of custom.

Late in his life, suffering from extreme ill health, his specimens were saved thanks to contributions from Adam Sedgwick, William Buckland, Lord Fitzwilliam and notables who had become aware of the plight of this extraordinary autodidact.

Very good condition; age-darkened and somewhat worn at the edges; postage stamp removed.