THE INVENTION OF THE MICROMETER, AND THE ORIGIN OF PRECISION ASTRONOMY

THE INVENTION OF THE MICROMETER, AND THE ORIGIN OF PRECISION ASTRONOMY

1. TOWNELEY, Richard

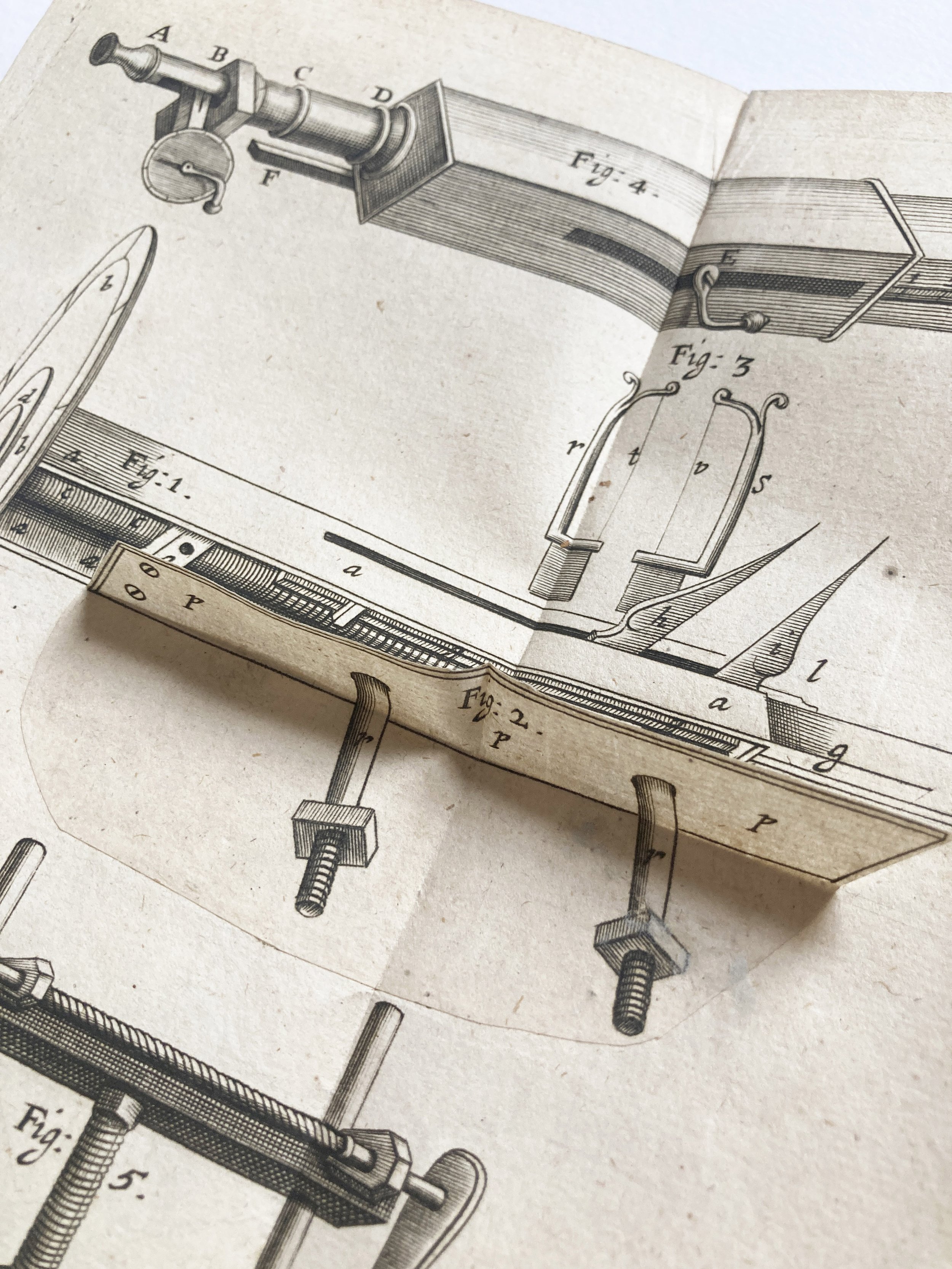

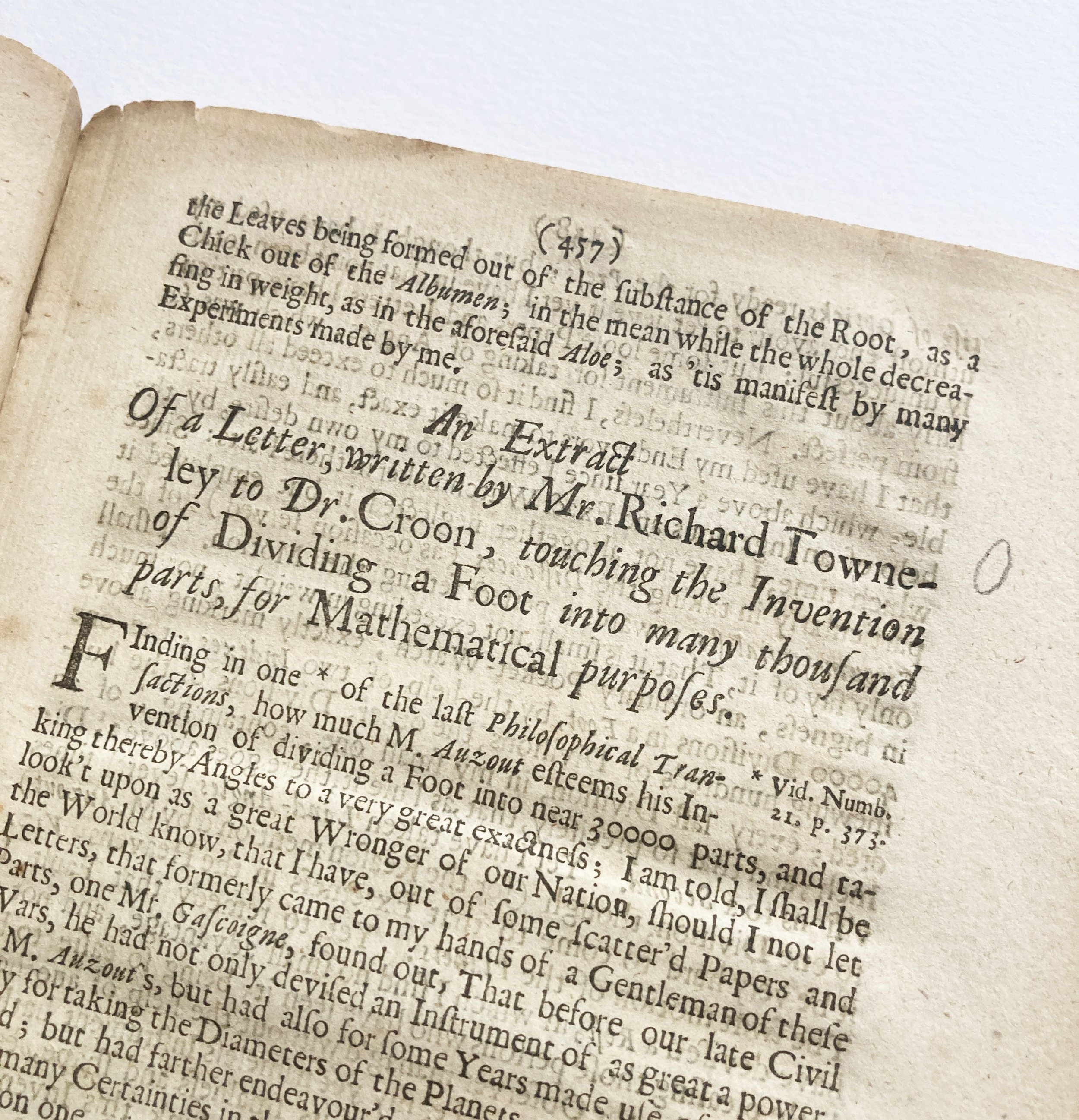

‘An Extract of a Letter, Written by Mr. Richard Towneley to Dr. Croon, Touching the Invention of Dividing a Foot into Many Thousand Parts, for Mathematical Purposes; HOOKE, Robert, ‘More Wayes for the Same Purpose, Intimated by M. Hook’, Philosophical Transactions No. 25 (1667), pp. 457–459

2. HOOKE, Robert

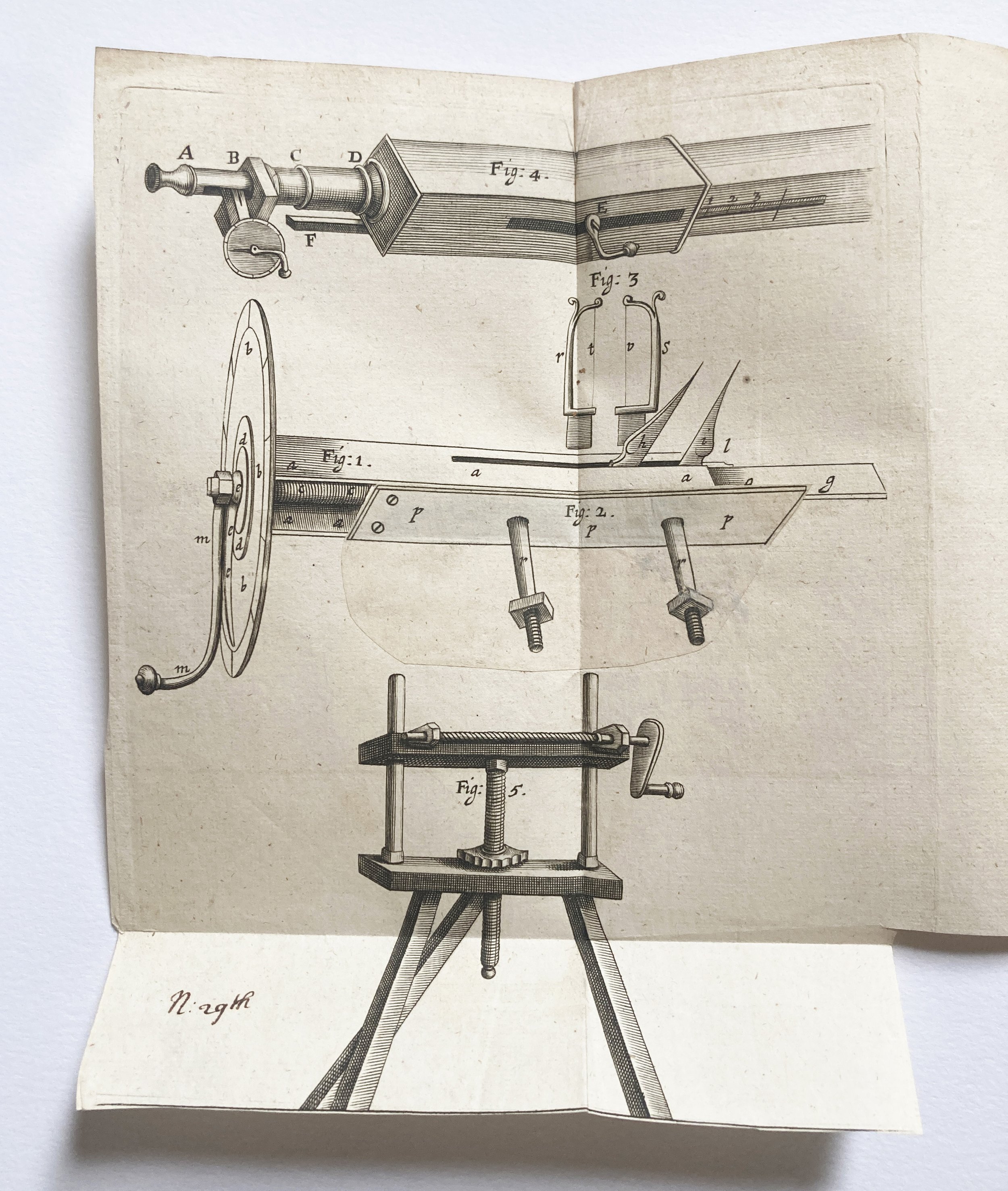

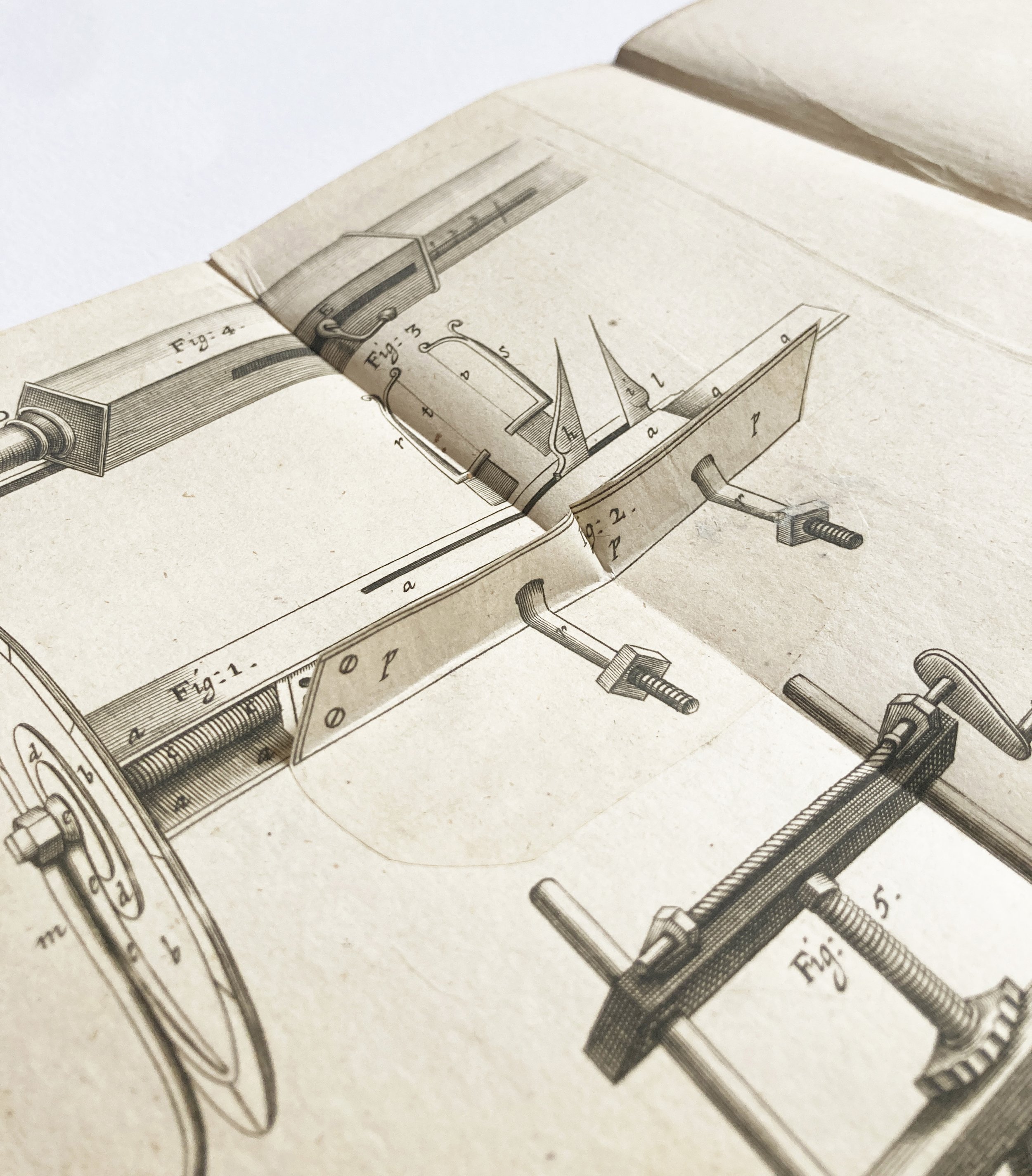

‘A Description of an Instrument for Dividing a Foot into Many Thousand Parts, and Thereby Measuring the Diameters of Planets to a Great Exactness, &c. as It Was Promised, Numb. 25’, Philosophical Transactions, No. 29 (1667), pp. 541-544 [WITH FOLDING PLATE]

Colophon: "Printed by T.N. for John Martyn at the Bell, a little without Temple-Bar, Printer to the Royal Society, 1667"

Small 4to

Two complete single issues of the Philosophical Transactions, containing the first description of the micrometer, with a fine 'interactive' illustration

A decisive moment in the history of science: William Gascoigne invents the micrometer, communicated here by Richard Towneley and Robert Hooke in two issues of the Philosophical Transactions for 1667 (nos 25 & 29).

Modern precision astronomy has its origins in the work of the ‘northern astronomer’ William Gascoigne (c.1612–1644), as described here in two very early issues of the Philosophical Transactions.

Inspired by the work of Johannes Kepler, Gascoigne – together with Jeremiah Horrocks, William Crabtree and Richard Towneley – studied astronomical phenomena from the 1630s until his early death in 1644. All four were based in the north of England: Gascoigne at Leeds, Horrocks near Liverpool, Crabtree near Manchester and the patron Towneley at Towneley Hall, near Burnley.

Gascoigne’s path to precision measurement was fortuitous: one day while observing he noticed that a strand of a spider’s web could be brought into focus to mark a precise line in the field of view. Around 1638 Gascoigne devised his micrometer, consisting of two fine wires brought closer together or further apart by means of a screw of known pitch. Together with the focal length it is possible to calculate the size of astronomical objects with this set-up.

Then, in 1666, the French astronomer Adrien Auzout wrote to the Royal Society to describe his own micrometer, which was similar in design to Gascoigne’s. Towneley, who was in possession of a micrometer of Gascoigne’s design, wrote a strongly worded letter to Society, published as No. 1 above. Towneley claimed Gascoigne’s priority and gave a brief description of the instrument, an example of which he then sent to London. Hooke created his own version of the micrometer and wrote a thorough description, published in No. 2. Perhaps the most significant feature of Hooke’s description is the remarkable engraving of the micrometer, which reveals aspects of its design not covered in the text. Moreover, the engraving is a piece of paper engineering in its own right: it shows two aspects of the design by means of an ingenious flap, which allows exterior and interior views.

The micrometer was immediately put to use by Hooke and, more importantly, John Flamsteed, who used one extensively in the creation of his masterpiece Historiae coelestis, begun in 1676. In various forms, the micrometer has been central to precision astronomer ever since, and has transformed scientific understanding of the nature of celestial objects, from the sun, moons and planets in our solar system to distant stellar objects, nebulae and comets.

Condition:

Both single issues are complete; pages in good to very good condition; disbound from a sammelband; the plate to No. 2 loose but in excellent condition. Pages uniformly age-darkened, with some wear to the edges. These issues are in an unusually good state of preservation and have been left unrestored, though they could be bound into modern wraps or, perhaps better, housed in a custom folder or box.

Literature:

– LaCour, L. J. & Sellers, D., ‘William Gascoigne, Richard Towneley, and the micrometer’, Antiquarian Astronomer 10 (2016), pp. 38–49

– Sellers, David, In Search of William Gascoigne, Seventeenth Century Astronomer (New York: Springer, 2012)

– Cooper, Michael; Hunter, Michael (eds), Robert Hooke: Tercentennial Studies (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006)